Former TEDMED editor Pritpal Tamber was an MD frustrated by the lack of empathy he felt innovators showed towards people’s lived realities. He’s decided to do something about that.

Pritpal S Tamber (facing) speaking with Tony Iton, Senior VP for Healthy Communities at The California Endowment.

Growing up in a working-class community in England, Pritpal S Tamber was “a nerd with good exam results.” Those results led him to medical school – and from there a winding career path that took him from medical journals to tech startups to where he is today – as a healthcare visionary, co-founder and CEO of Bridging Health & Community.

In an industry with no shortage of talk around innovation and patient-centered care, Tamber comes across as the real deal – deeply thoughtful, inquisitive, critical and full of genuine concern.

He’s also the kind of guy who demands to be heard. He speaks with passion and urgency about his frustrations as a medical professional and the enormous opportunities for improvement in a field that he feels talks about innovation a lot without delivering.

But let’s go back.

Entering medical school, Tamber expected an intellectually stimulating environment that would open the doors of his mind, but instead found a system governed by textbooks that was “deeply unsatisfying.”

“You spend six years getting an education to work in a system that nobody really endorses and everyone tells you is crap,” he said. “They put you in a cage – and that always jarred me.”

In this fourth year of studies Tamber won a scholarship at the British Medical Journal where he learned the importance of peer review, editing and clinical information.

“It was the first time I felt liberation – getting underneath the assumptions of the system and the textbooks you have to learn to what is knowledge,” he said. He graduated a year later and started clinical practice, serving a couple years before he was asked to join a publishing company in 1999 called BioMed Central, one of the first of its kind in internet publishing. There he spent five years figuring out how to widen the distribution of knowledge within the field and pursuing “the utopian idea that everyone should have access to knowledge.”

“The amount of barriers is phenomenal,” he said. “It was eye opening to me how existing systems stop change – change that might offer societal good but have no commercial implications for the existing system.”

““It was eye opening to me how existing systems stop change.””

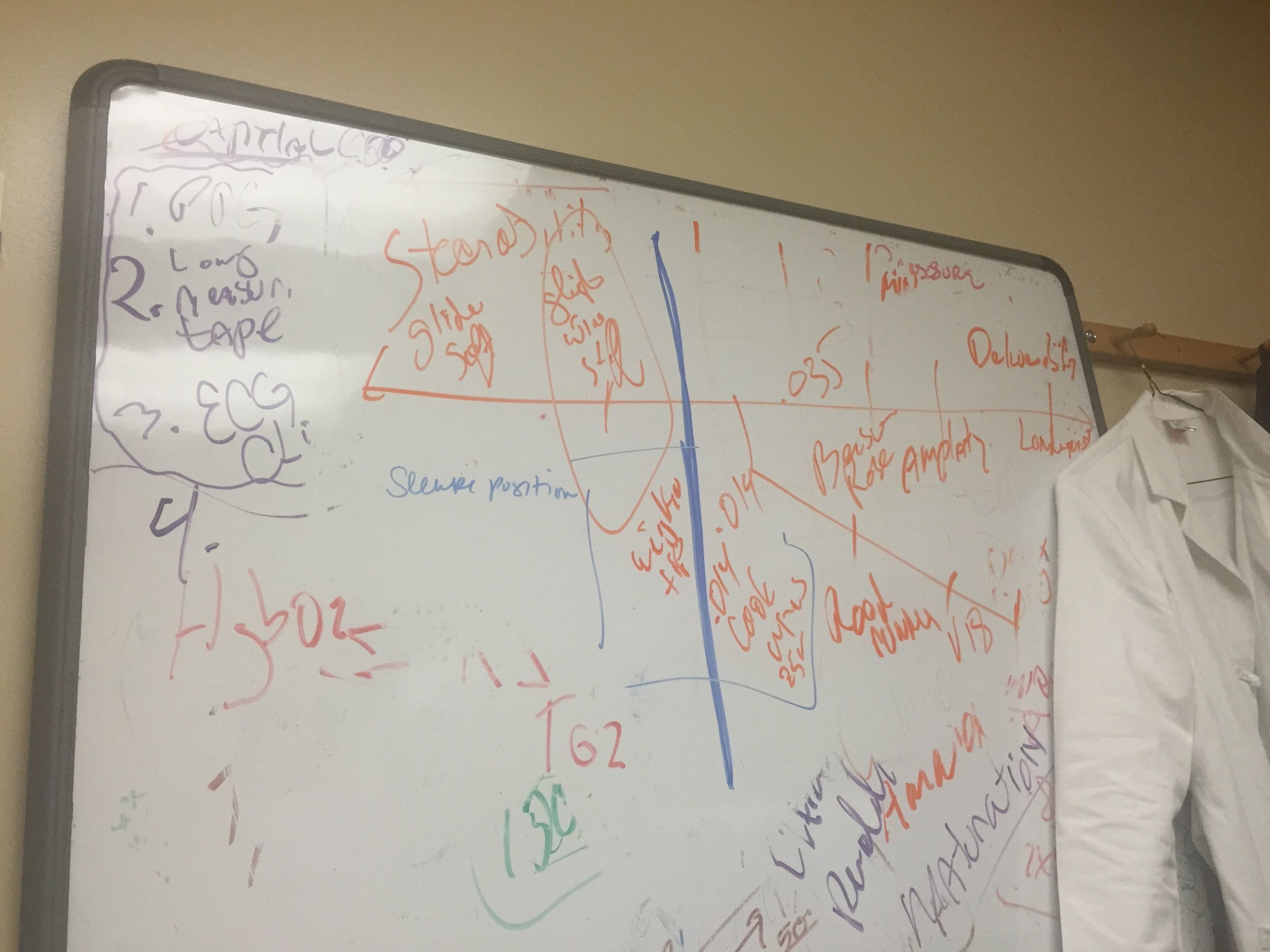

Tamber went into clinical publishing that was integrated with EMR systems and confronted the challenge of structuring knowledge in a way that aids real-time clinical decision making. He learned that the IT infrastructure required for knowledge to be useful was not there, but the system was brilliant for billing. “They’re basically billing systems with a clinical interface on top.”

The experience also led Tamber to other conclusions regarding the application of technology in healthcare. Most importantly, he discovered it’s incredibly hard to improve how a health system works with just knowledge and IT – no matter how good it is. “There’s all sorts of relationship stuff that needs to be worked on outside of anything you can do with IT.”

“When you look at innovation in health it’s all tech-driven, but trying to make any real change is all about improving relationships within that system. In a technocratic world people forget that relationships are at the core of complex systems.”

Tamber became interested in the bigger question: What stops innovation? He decided it had less to do with whether or not there was venture capital available and the mechanics, and more about the human side.

So he quit his job to become a consulting VP of medicine to startups trying to get to clinical innovation.

There he found that while he could help people figure out how the technology works, they almost always got the value proposition – the story – wrong.

Around that time Tamber was approached by TEDMED to become their physician editor. He put together their 2013 program. Working for an organization that was more interested in ideas than innovation per se proved to be an interesting intellectual exercise. “An idea doesn’t necessarily have to be realized,” he said. “There’s a different editorial process in understanding if an idea is worth sharing. The work TEDMED is doing of critically assessing ideas is really important to change – and that’s generally absent in healthcare.”

““In a technocratic world people forget that relationships are at the core of complex systems.””

So Tamber did what any MD with a background in editing and technology would – he started a blog. The purpose was to mine the disconnect between health systems and communities. His own background influences his critique.

“I was acutely aware in medical school that they didn’t have a clue about what it means to come from a working-class environment,” he said. “They offer all this advice about better food, exercise, sleep – which isn’t practical for people in these situations. There’s a fundamental disconnect of healthcare with where people really are in their lives.”

Tamber’s focus and passion became trying to understand how a health system can work with local communities in difficult social circumstances. This started him on a quest to identify practitioners around the world who were “trying to do stuff.”

“I only wanted to talk to doers because it felt to me that public health and academia are filled with ideas but very few people who are actually doing anything,” he said. “All those people talking about it for years from the perspective of social justice and health equity and – so what? How do you actually do any of what they advocate?”

The 2016 Meeting of the Creating Health Collaborative.

If the community has no sense of control or purpose and no understanding of their own justice in society, Tamber challenges, why would they try to have a better life? What would be the point? “People take care of themselves because they have a sense of their future. If you don’t have a sense of your future, why would you care about health?”

It’s not without some disdain that Tamber evokes the example of people in health who talk about patients needing to go to the gym or the farmer’s market. He urges a different type of conversation. One that allowed people to define for themselves what health means. “If you allow that conversation to be authentic, you’ll find that health means things like safety, belonging, feeling connected, having access to opportunity. Diabetes usually isn’t the first thing they talk about.”

The question became: “How do you engage a community in their health when their very definition of health is different from yours and that of the health system?”

That work led to a series of interviews and meetings with select doers who he ended up calling the Creating Health Collaborative, an international group of innovators exploring health from the perspective of people and communities.

“The discourse in healthcare continues to be around virtual surgery, genotyping and sexy, tech-driven knowledge around health,” Tamber said. “People with power continue to dominate the discourse around health and people without power have no voice to say – ‘Can we just have a decent school for our kids?’”

“If you just say, ‘Hey fat person, stop being fat – it’s never going to work. But that’s my one-sentence explanation of what public health has become. It keeps kidding itself that technology is what’s going to change that. It’s still an information intervention, and they haven’t been working for four decades.”

Tamber hopes to flip that conversation with the first symposium of Bridging Health & Community – an event that will feature a diverse range of speakers from an urban planner to a political scientist to the father of social epidemiology. “There’s going to be no theory up there,” he said. “Everyone there has to illustrate practically a part of this work.”

“We continue to invest in technologies that don’t get to the communities we most need to reach and we haven’t shifted our thinking,” Tamber says. “Where is a forum for thinking in health? That’s why I created this.”

Bridging Health & Community’s Symposium, Community Agency & Health, takes place May 15-16 in Oakland, CA. To learn more and purchase tickets, go here: Community Agency and Health Symposium